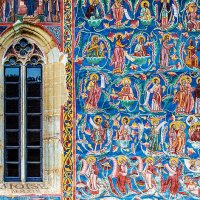

In Bucovina each important life moment is surrounded by old traditions. Moments as birth, wedding, or burial are marked by both Chistian and pre Christian customs and rites.

In Bucovina each important life moment is surrounded by old traditions. Moments as birth, wedding, or burial are marked by both Chistian and pre Christian customs and rites.

Childbirth is a significantly joyful event for every family. In those moments, the mother and the midwife would perform a series of rites. The parents would be involved in a series of practices meant to protect the infant from the dark forces and to integrate the newborn in society.

The infant had to be protected from the evil eye, thus the midwife would tie a red ribbon on the infant’s right arm.

To protect it from diseases and evil, coals would be cooled in a bath.

As a rite, that bath would be the infant’s first bath.

Things would be brought to the infant, such as: coins, basil, sugar, so that the infant would grow up to be: “Precious as silver / sweet as honey/ good like bread/ healthy as an egg, Red as a rose/ attractive like basil/ White as milk.”

The wedding was an event of utmost importance to the village life in Bucovina. It has multiple implications, both for the individual and the rural community life. Compared to birth and burial, the wedding is a voluntary act governed by love, wealth, obedience towards the rigors of tradition. The main events concerning the wedding ceremony are the courtship, the wedding call, the bride’s feast, the dowry game, showing the bride before the attendants, asking the parents for pardons, bowing, the way/exit from church.

Asking the parents for pardons is an extremely important phase of the wedding ritual. The bride and the groom had to ask for pardons from their parents, siblings, and relatives, because they would oftentimes move to a different household. The bond between the lovers was acceptable only if the parents gave their consent.

The best man would ask for pardon in the name of the young through an oration:

“Bride, apologize to your lovely momma/ from the bed of flickers/

From your good ol’ pa/ from the bed of bland food/ from your younger sister/

From the bed of roses/ from your younger brothers / be a healthy mother/

If you weren’t happy to see me in your abode like a beautiful carnation”.

Although there were many fundamental changes in the village life of Bucovina, we can still find numerous customs that lasted in time.

As usual for Romanians, burial rites in Bucovina reflect the mindset that peasants had towards death as a natural phenomenon. In the popular belief, death is the last season, the winter of life, returning to the earth from which new slips will sprout in spring. When a family member died, the bells would toll thrice a day (until burial day). The family members would wear black traditional attire; women would have their hair loose or wear black head kerchiefs. Men wouldn’t wear hats and would have their facial hair unshaven. After the bath of the deceased, he would be clothed in the clothes prepared before his passing and he would be put in a coffin so that the people would say goodbye. In the coffin there had to be some tree bark, white linen and a pillow. The eyes of the deceased would be closed, not to see the bereavement surrounding him, and the mirrors would be covered or turned towards the wall. As a rite, mourning would be done by family members, or in some cases, by female mourners outside family. They would sit inside or outside the house, near the windows, and behind the carriage used to carry the deceased to the burial site.

The burial would be held the third day – a moment of grief and mourning for the family and the entire community. According to the rules of conduct imposed by the rural social life, not only family members were involved in the burial organisation, but also the community members. On the day of the burial, the sieve was prepared according to the area. They would put in a bucket a plum branch embellished with shapes made of bread dough, walnuts, apples, and candies. Leading the convoy were men waving flags embellished with cloth and braided bread. They were followed by those who carried the tree for burial, and later followed by the ox-driven carriage and the bereaved family, relatives, and villagers. After the ceremony, boiled wheat and sugar would be given to the attendants. At the house of the deceased, there would be a proper ceremony, represented by a moment of solidarity for the family who lost a member.